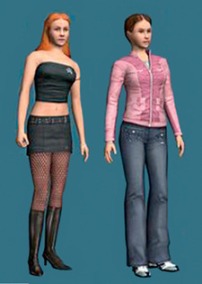

Avatars are all the rage these days. Facebook profile pics, World of Warcraft and EVE Online characters, Second Life and OpenSim personas—these are just a few examples of a growing phenomenon. We all seem to have some sort of digital representation of ourselves that we project into cyberspace—and we spend a fair amount of time designing and customizing them, getting their appearances just right.

Avatars are all the rage these days. Facebook profile pics, World of Warcraft and EVE Online characters, Second Life and OpenSim personas—these are just a few examples of a growing phenomenon. We all seem to have some sort of digital representation of ourselves that we project into cyberspace—and we spend a fair amount of time designing and customizing them, getting their appearances just right.

Who can blame us, really? After all, they are us, the digital faces we present to the virtual world. That doesn’t mean they have to perfectly replicate our real-world identities, though. In fact, the beauty of designing an avatar is the ability to get creative, to choose exactly who we want to be, to build our ideal selves.

At first blush, it would appear that this is a one-way exchange: through the creative process, we affect the avatar, which we then use to interact with the virtual world. Certainly, with things like static photos and images, this is the case. However, with respect to a 3D digital persona that responds to our commands, it gets a little more complicated. In fact, as several researchers are discovering, situations that we experience virtually through our avatars can impact and even alter our reality.

Palo Alto research scientist Nick Yee dubbed this the Proteus Effect, after the Greek sea god Proteus, who could assume many different forms (and whose name lends itself to the adjective protean—changeable). He first described it in 2007 while studying how an avatar’s appearance and height affected the way people behaved in the virtual world. In his initial research, Yee provided study subjects with avatars that were attractive or unattractive, tall or short, and then watched them interact with a virtual stranger (controlled by one of Yee’s lab assistants). Here’s what Yee’s team discovered:

Palo Alto research scientist Nick Yee dubbed this the Proteus Effect, after the Greek sea god Proteus, who could assume many different forms (and whose name lends itself to the adjective protean—changeable). He first described it in 2007 while studying how an avatar’s appearance and height affected the way people behaved in the virtual world. In his initial research, Yee provided study subjects with avatars that were attractive or unattractive, tall or short, and then watched them interact with a virtual stranger (controlled by one of Yee’s lab assistants). Here’s what Yee’s team discovered:

We found that participants who were given attractive avatars walked closer to and disclosed more personal information to the virtual stranger than participants given unattractive avatars. We found the same effect with avatar height. Participants in taller avatars (relative to the virtual stranger) negotiated more aggressively in a bargaining task than participants in shorter avatars.”

Yee’s work demonstrated clearly that an avatar’s appearance could change how someone acted within a virtual environment and interacted with its residents.

Okay, so what? It’s interesting, but what relevance does it have to the real world?

In 2009, Yee asked the same question: did changes in virtual-world behavior translate to physical reality? He revisited his 2007 study, adding another task: After concluding their virtual interaction, Yee had each participant create a personal profile on a mock dating site and then, from a group of nine possible matches, select the two s/he’d most like to get to know. Without fail, Yee says,

… we found that participants who had been given an attractive avatar in a virtual environment chose more attractive partners in the dating task than participants given unattractive avatars in the earlier task. This study showed that effects on people’s perceptions of their own attractiveness do seem to linger outside of the original virtual environment.”

The Proteus Effect has been credited with more than just creating more aggressive negotiators or making people feel better about themselves: weight loss, substance abuse treatment, environmental consciousness, perception of obstacles… all affected by people’s experiences through their avatars within virtual reality. According to Maria Korolov, founder and editor of the online publication Hypergrid Business—and who’s been studying virtual worlds since their inception—people who exercise within a virtual world…

… will exercise an hour more on average the next day in real life, because they think of themselves as an exercising-type person. It changes the way you think.”

Researchers at the University of Kansas Medical Center back this up. A weight loss study there found that people who lost weight either through virtual or face-to-face exercise programs were more effective at managing their weights if they took part in maintenance programs delivered through Second Life.

Regarding substance abuse, Preferred Family Healthcare, Inc., found that treatment outcomes for participants in their virtual programs were as good as or better than those for people who took part in real-life counseling. More significantly, fewer people dropped out of virtual treatment—vastly so: virtual programs saw a 90 percent completion rate, as opposed to 30-35 percent completion for programs at a traditional, physical facility.

Environmental consciousness may seem like a stretch, but researchers at Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab found that people who felled a massive, virtual sequoia used less paper in the real world than those who only imagined cutting down a tree.

Environmental consciousness may seem like a stretch, but researchers at Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab found that people who felled a massive, virtual sequoia used less paper in the real world than those who only imagined cutting down a tree.

And perhaps the most interesting example, a study at the University of Michigan showed that participants who saw that a backpack was attached to an avatar consistently overestimated the heights of virtual hills—but only if they’d created the avatar themselves. Participants assigned an avatar by the researchers were much more accurate in their estimations. Said S. Shyam Sundar, Distinguished Professor of Communications and co-director of the Media Effects Research Laboratory, Penn State, who worked on the study,

You exert more of your agency through an avatar when you design it yourself. Your identity mixes in with the identity of that avatar and, as a result, your visual perception of the virtual environment is colored by the physical resources of your avatar… If your avatar is carrying a backpack, you feel like you are going to have trouble climbing that hill, but this only happens when you customize the avatar.”

Of course, there is a dark side to the Proteus Effect. A study co-written by Jorge Peña, assistant professor in the College of Communication at the University of Texas, Austin, Cornell University Professor Jeffrey T. Hancock, and graduate student Nicholas A. Merola (also at Austin), showed that avatars could be used to prime negative responses in users within a virtual world. In two separate studies, researchers randomly assigned participants dark- or white-cloaked avatars, or avatars wearing physician or Ku Klux Klan-like uniforms. They were also asked to write a story about a picture or play a video game on a virtual team and then come to consensus on dealing with infractions. Those in the dark cloaks or KKK robes consistently showed negative or anti-social behavior. What really causes concern, though, is that they were completely unaware that they’d been primed to do so. According to Peña,

By manipulating the appearance of the avatar, you can augment the probability of people thinking and behaving in predictable ways without raising suspicion. Thus, you can automatically make a virtual encounter more competitive or cooperative by simply changing the connotations of one’s avatar.”

Behavior modification through manipulation of appearance is nothing new: Traditional, face-to-face psychological experiments have shown that changes in dress can affect a person’s behavior or perception of themselves. That this also happens in the virtual world says something interesting about the human brain and its ability to distinguish reality from virtuality.

It should also give us pause. We’re rushing headlong into a brave, new virtual world, and it seems all but unstoppable. This, in itself, is not a bad thing. However, as we move forward, we would do well to proceed deliberately and with caution. Our history is rife with examples of decisions made ignorant of the potential outcome, and good intentions corrupted. If we are going to plunge into the virtual, we must consider the consequences—intended or otherwise—that our choices, and our actions, may beget.

You can read a summary of Nick Yee’s work here.

For a discussion of the University of Kansas study, check this link.

You can read about the Preferred Family Healthcare study here.

The Virtual Human Interaction lab study is here.

Check out the University of Michigan study here.

And you can find a discussion of the potential negative aspects of avatar manipulation here.

Last weekend, videogames lost their father: On Saturday, December 6, at the age of 92, Ralph Baer—inventor of the videogame and progenitor of a 100-billion-dollar global industry and an obsession, hobby, or pastime for more than a billion people—passed away.

Last weekend, videogames lost their father: On Saturday, December 6, at the age of 92, Ralph Baer—inventor of the videogame and progenitor of a 100-billion-dollar global industry and an obsession, hobby, or pastime for more than a billion people—passed away.

The game is slated for release later this year, so I haven’t had a chance to play it yet. However, reviewers at Polygon were treated to a preview by the developer, and even watching the gameplay is harrowing. This War of Mine is dark—literally and figuratively—and intense: everything about it, from the environment to the gameplay, is designed to engender unease. The game sets you on edge from moment one and holds you there for as long as you can stand to play.

The game is slated for release later this year, so I haven’t had a chance to play it yet. However, reviewers at Polygon were treated to a preview by the developer, and even watching the gameplay is harrowing. This War of Mine is dark—literally and figuratively—and intense: everything about it, from the environment to the gameplay, is designed to engender unease. The game sets you on edge from moment one and holds you there for as long as you can stand to play. For a few years now, I’ve been raving about Crystal Dynamics’ reboot of Tomb Raider and their reimagining of its protagonist, Lara Croft, from a scantily clad, hypersexualized, adolescent male fantasy to a more realistic, appropriately dressed and anatomically restrained, tough, gritty survivor (see my earlier post

For a few years now, I’ve been raving about Crystal Dynamics’ reboot of Tomb Raider and their reimagining of its protagonist, Lara Croft, from a scantily clad, hypersexualized, adolescent male fantasy to a more realistic, appropriately dressed and anatomically restrained, tough, gritty survivor (see my earlier post  The video begins, not with Lara escaping death or brutally overcoming an attacker, but with her in therapy. You read that right: therapy. We see her on the edge of a chair, cloaked in a hoodie, head downcast. As the therapist talks, Lara digs her fingers into the upholstery, clenches her fist, bounces her leg. She can’t sit still. She’s clearly anxious and uncomfortable. This is not the bulletproof heroine we’ve come to expect, casually shaking off the death she’s dealt. Lara has experienced horrors the likes of which most of us can’t imagine, and she’s been deeply affected by them. But neither is she a broken woman. Battered and scarred yet alive, she’s found away to exist in between. Her therapist continues:

The video begins, not with Lara escaping death or brutally overcoming an attacker, but with her in therapy. You read that right: therapy. We see her on the edge of a chair, cloaked in a hoodie, head downcast. As the therapist talks, Lara digs her fingers into the upholstery, clenches her fist, bounces her leg. She can’t sit still. She’s clearly anxious and uncomfortable. This is not the bulletproof heroine we’ve come to expect, casually shaking off the death she’s dealt. Lara has experienced horrors the likes of which most of us can’t imagine, and she’s been deeply affected by them. But neither is she a broken woman. Battered and scarred yet alive, she’s found away to exist in between. Her therapist continues: PTSD. That’s what he’s talking about. This is classic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Lara is suffering from something that affects nearly eight million American adults, that’s all too common among veterans of war and survivors of abuse, that can strike at any age, and that can tear families and communities apart. She has PTSD, and she’s dealing with it. That a video game is so directly dealing with this is extraordinary. And that Lara is working through and recovering from the trauma of her ordeal may provide hope to those facing traumas of their own. I’ll leave you with the experience of a young woman suffering from PTSD who, while playing Tomb Raider, discovered just that:

PTSD. That’s what he’s talking about. This is classic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Lara is suffering from something that affects nearly eight million American adults, that’s all too common among veterans of war and survivors of abuse, that can strike at any age, and that can tear families and communities apart. She has PTSD, and she’s dealing with it. That a video game is so directly dealing with this is extraordinary. And that Lara is working through and recovering from the trauma of her ordeal may provide hope to those facing traumas of their own. I’ll leave you with the experience of a young woman suffering from PTSD who, while playing Tomb Raider, discovered just that: Are video games art? It’s a question that’s been posed many times, particularly over the last decade as the power and speed of graphics processors and gaming machines (exemplified by the Xbox One, PlayStation 4 and Wii U) have reached the point where digital artists have virtually unlimited ability to give their imaginations free rein, allowing them to create and deliver visual landscapes of stunning beauty, richness, and depth. Many of these worlds are so engrossing that gamers regularly find themselves captivated, forgetting, for a moment, to play and pausing to admire the view—to, in essence, stop and smell the virtual roses.

Are video games art? It’s a question that’s been posed many times, particularly over the last decade as the power and speed of graphics processors and gaming machines (exemplified by the Xbox One, PlayStation 4 and Wii U) have reached the point where digital artists have virtually unlimited ability to give their imaginations free rein, allowing them to create and deliver visual landscapes of stunning beauty, richness, and depth. Many of these worlds are so engrossing that gamers regularly find themselves captivated, forgetting, for a moment, to play and pausing to admire the view—to, in essence, stop and smell the virtual roses. I suspect that no matter who you ask, you’ll hear a variety of responses, and most won’t be a simple yes or no—and the debate will probably never be settled (at least not to anyone’s satisfaction). Nevertheless, museums around the country are throwing their hats in the ring through a traveling exhibit entitled, appropriately, The Art of Video Games. And though it doesn’t claim to be the final word on the subject, it aims to at least push the conversation forward. The exhibit kicked off in March of 2012, at the

I suspect that no matter who you ask, you’ll hear a variety of responses, and most won’t be a simple yes or no—and the debate will probably never be settled (at least not to anyone’s satisfaction). Nevertheless, museums around the country are throwing their hats in the ring through a traveling exhibit entitled, appropriately, The Art of Video Games. And though it doesn’t claim to be the final word on the subject, it aims to at least push the conversation forward. The exhibit kicked off in March of 2012, at the  Which is where I’m writing this, books in hand and ready to extoll the social, cultural, and, yes, artistic value of video games. It’s not that I feel any particular need to validate them to professional critics or anyone else who staunchly refuses to see any merit in the form (though I do have game developer friends, and I’d like to see their work taken seriously and truly appreciated). It’s just that I truly believe that they are art—and further, that when you really spend time with games and explore what goes into creating them, the issues developers are attacking, and the messages they’re trying to communicate, that conclusion becomes inescapable. Take Jonathan Blow’s Braid, for example, which deals with forgiveness and desire; Ryan Green’s That Dragon, Cancer, an attempt to cope with his own son’s terminal illness; or Flower, by Jenova Chen, which explores our relationship to nature. As you progress through each of these games—as well as a host of others for which there isn’t the time or space to do them justice here (Bioshock, Super Meat Boy, and Deus Ex, just to name three)—the story gradually falls into place, and you gain insight into the developer’s world view. Even the infamous and, I would argue, mostly misunderstood Grand Theft Auto series reveals some scathing social commentary for those who care to look just a bit below the surface. Some games, like Fez, are boundlessly joyful and beautifully presented, and some, like Myst, Riven, the Halo series, the recent reboot of Tomb Raider, Uncharted 2, and the unfortunately canceled Star Wars 1313 are simply gorgeous to behold, their worlds rendered in artistic splendor, filled with music befitting a symphony hall. By any definition you care to apply, these games—and many others—are, quite simply, art.

Which is where I’m writing this, books in hand and ready to extoll the social, cultural, and, yes, artistic value of video games. It’s not that I feel any particular need to validate them to professional critics or anyone else who staunchly refuses to see any merit in the form (though I do have game developer friends, and I’d like to see their work taken seriously and truly appreciated). It’s just that I truly believe that they are art—and further, that when you really spend time with games and explore what goes into creating them, the issues developers are attacking, and the messages they’re trying to communicate, that conclusion becomes inescapable. Take Jonathan Blow’s Braid, for example, which deals with forgiveness and desire; Ryan Green’s That Dragon, Cancer, an attempt to cope with his own son’s terminal illness; or Flower, by Jenova Chen, which explores our relationship to nature. As you progress through each of these games—as well as a host of others for which there isn’t the time or space to do them justice here (Bioshock, Super Meat Boy, and Deus Ex, just to name three)—the story gradually falls into place, and you gain insight into the developer’s world view. Even the infamous and, I would argue, mostly misunderstood Grand Theft Auto series reveals some scathing social commentary for those who care to look just a bit below the surface. Some games, like Fez, are boundlessly joyful and beautifully presented, and some, like Myst, Riven, the Halo series, the recent reboot of Tomb Raider, Uncharted 2, and the unfortunately canceled Star Wars 1313 are simply gorgeous to behold, their worlds rendered in artistic splendor, filled with music befitting a symphony hall. By any definition you care to apply, these games—and many others—are, quite simply, art.

Like painting, sculpture, writing, photography, and music, video games range from simple to complex, derivative to revolutionary, and profane to sublime. They can elicit feelings of hope and fear; longing and despair; grief, loss, joy, and love. They can heal our bodies and open our minds. And if we let them, they can teach us about the world, about each other, and about ourselves. In the final analysis, that is the mark of true art.

Like painting, sculpture, writing, photography, and music, video games range from simple to complex, derivative to revolutionary, and profane to sublime. They can elicit feelings of hope and fear; longing and despair; grief, loss, joy, and love. They can heal our bodies and open our minds. And if we let them, they can teach us about the world, about each other, and about ourselves. In the final analysis, that is the mark of true art. There’s also an in-depth look at the artistic aspirations of one particular game, Journey—developed by Jenova Chen’s studio Thatgamecompany (of Flower fame)—in

There’s also an in-depth look at the artistic aspirations of one particular game, Journey—developed by Jenova Chen’s studio Thatgamecompany (of Flower fame)—in

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine published a study that concluded the following: medical errors in the US cost the lives of as many as 98,000 people each year (and run up a $17- $29 billion bill to boot). Ten years later, the

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine published a study that concluded the following: medical errors in the US cost the lives of as many as 98,000 people each year (and run up a $17- $29 billion bill to boot). Ten years later, the

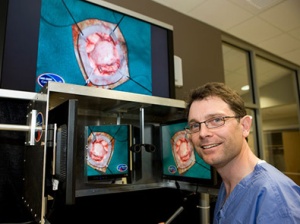

You can also customize a simulation to closely reflect reality, matching the conditions and characteristics of actual patients. In 2009, Halifax neurosurgeon

You can also customize a simulation to closely reflect reality, matching the conditions and characteristics of actual patients. In 2009, Halifax neurosurgeon  What can surgeons do for six minutes that enhances performance, reduces errors, and improves patient outcomes?

What can surgeons do for six minutes that enhances performance, reduces errors, and improves patient outcomes? Dr. Rosser proved this in 2002, while practicing at Beth Israel Medical Center. He had 33 surgeons participate in a three-month study that involved, among other activities, playing a series of video games before simulating laparoscopic surgery. About half of the participants had a history of game play, though all of them played throughout the study. Researchers compared the results between participants, as well as against non-gaming colleagues. Across the board, they found that surgeons who played video games were faster and more accurate than those who didn’t—dramatically so: at the low end of the skill spectrum, gaming docs made a third fewer errors and were a quarter faster than their non-playing counterparts. Among participants, the most skilled surgeon gamers were nearly half again as accurate and more than a third faster than those at the bottom of the heap. Further, after controlling for extent of training and number of cases completed, the best predictors of surgical success were video game skill and amount of past gaming experience. Said surgeon and participant Asaf Yalif,

Dr. Rosser proved this in 2002, while practicing at Beth Israel Medical Center. He had 33 surgeons participate in a three-month study that involved, among other activities, playing a series of video games before simulating laparoscopic surgery. About half of the participants had a history of game play, though all of them played throughout the study. Researchers compared the results between participants, as well as against non-gaming colleagues. Across the board, they found that surgeons who played video games were faster and more accurate than those who didn’t—dramatically so: at the low end of the skill spectrum, gaming docs made a third fewer errors and were a quarter faster than their non-playing counterparts. Among participants, the most skilled surgeon gamers were nearly half again as accurate and more than a third faster than those at the bottom of the heap. Further, after controlling for extent of training and number of cases completed, the best predictors of surgical success were video game skill and amount of past gaming experience. Said surgeon and participant Asaf Yalif, Surgeons can’t operate on live patients every day. It’s a numbers game: there just aren’t enough people who need surgery to go around. Other means of honing surgical skills—such as simulators—are therefore critical. The catch is that typical medical simulators run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars—an expense that can be hard for many hospitals to swallow. A game console—like the Wii, Xbox, or Playstation—costs a fraction of that, and provides a viable and effective way to keep surgeons sharp.

Surgeons can’t operate on live patients every day. It’s a numbers game: there just aren’t enough people who need surgery to go around. Other means of honing surgical skills—such as simulators—are therefore critical. The catch is that typical medical simulators run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars—an expense that can be hard for many hospitals to swallow. A game console—like the Wii, Xbox, or Playstation—costs a fraction of that, and provides a viable and effective way to keep surgeons sharp. In my previous two posts, I talked a lot about avatars and some of the rather intriguing and exciting developments happening regarding virtual worlds. In brief, both are evolving far beyond what early digital pioneers could have envisioned when they took their first steps into virtual reality. We have the ability today, as demonstrated by LucasArts’ E3 reveal of Star Wars: 1313, to render near-photo-realistic environments in real-time. Absolute photo-realism is a mere skip in time away—five years at the outside—and completely immersive, realistic virtual worlds experienced through any connected device are already on the horizon.

In my previous two posts, I talked a lot about avatars and some of the rather intriguing and exciting developments happening regarding virtual worlds. In brief, both are evolving far beyond what early digital pioneers could have envisioned when they took their first steps into virtual reality. We have the ability today, as demonstrated by LucasArts’ E3 reveal of Star Wars: 1313, to render near-photo-realistic environments in real-time. Absolute photo-realism is a mere skip in time away—five years at the outside—and completely immersive, realistic virtual worlds experienced through any connected device are already on the horizon. Very soon, in fact. Prototypes of The Oculus Rift VR headset show great promise in delivering fully-immersive 3D gaming to the masses. With it, you can climb into the cockpit of a star fighter and engage in ship-to-ship combat, surrounded on all sides by the vastness of space and the intensity of interstellar battle (as with EVE VR). Combine the Rift with the Wizdish omni-directional treadmill and a hands-free controller like the Xbox Kinect, and you can transform a standard first-person shooter into a full-body experience—allowing you to ditch the thumbsticks and literally walk through a game’s virtual environment, controlling your actions via natural motion of hands, feet, arms, legs, and head.

Very soon, in fact. Prototypes of The Oculus Rift VR headset show great promise in delivering fully-immersive 3D gaming to the masses. With it, you can climb into the cockpit of a star fighter and engage in ship-to-ship combat, surrounded on all sides by the vastness of space and the intensity of interstellar battle (as with EVE VR). Combine the Rift with the Wizdish omni-directional treadmill and a hands-free controller like the Xbox Kinect, and you can transform a standard first-person shooter into a full-body experience—allowing you to ditch the thumbsticks and literally walk through a game’s virtual environment, controlling your actions via natural motion of hands, feet, arms, legs, and head. Unlike the Oculus Rift, the Meta system includes physical control and also works in real space (not strictly a virtual gaming world). And unlike Google Glass, Meta creates a completely immersive virtual environment. According to a recent article by Dan Farber on CNET,

Unlike the Oculus Rift, the Meta system includes physical control and also works in real space (not strictly a virtual gaming world). And unlike Google Glass, Meta creates a completely immersive virtual environment. According to a recent article by Dan Farber on CNET, In my last post, I said that avatars were all the rage, and they are—and most likely will only become more so within the next five years. Why then? That’s when Philip Rosedale believes we’ll see intricately detailed virtual worlds that begin to rival reality. If you don’t know Rosedale, you know his work: back in 2000, he created the first massively multiuser 3D virtual experience. It was more alternate reality than game, and with perhaps a nod to his desire to build a world that would become an essential component of daily existence, Rosedale called his creation Second Life.

In my last post, I said that avatars were all the rage, and they are—and most likely will only become more so within the next five years. Why then? That’s when Philip Rosedale believes we’ll see intricately detailed virtual worlds that begin to rival reality. If you don’t know Rosedale, you know his work: back in 2000, he created the first massively multiuser 3D virtual experience. It was more alternate reality than game, and with perhaps a nod to his desire to build a world that would become an essential component of daily existence, Rosedale called his creation Second Life. That’s where we’re headed—rushing headlong towards, in fact—and Rosedale is at the fore in getting us there. At the recent Augmented World Expo in Santa Clara, CA, he dropped a few hints as to what his new company, High Fidelity, is cooking up. At its heart, it could be a 3D world that’s virtually indistinguishable from reality, offering a vastly increased speed of interaction, employing body tracking sensors for more life-like avatars, and applying the computing power of tens of millions of devices in the hands of end-users the world over. Within five years, he believes that any mobile device will be able to access and interact with photo-realistic virtual worlds in real time, with no discernable lag.

That’s where we’re headed—rushing headlong towards, in fact—and Rosedale is at the fore in getting us there. At the recent Augmented World Expo in Santa Clara, CA, he dropped a few hints as to what his new company, High Fidelity, is cooking up. At its heart, it could be a 3D world that’s virtually indistinguishable from reality, offering a vastly increased speed of interaction, employing body tracking sensors for more life-like avatars, and applying the computing power of tens of millions of devices in the hands of end-users the world over. Within five years, he believes that any mobile device will be able to access and interact with photo-realistic virtual worlds in real time, with no discernable lag. And this is today. Within five years, he told me, they’ll achieve absolute, indistinguishable-from-reality photo-realism. Regarding the ability of mobile devices to connect to the type of virtual world Rosedale envisions, he’s a little more conservative. In this case, the bottleneck isn’t computing power but the speed of Internet connectivity, which depends on more factors. Still, Libreri sees that being cleared within 10 years. And that’s it—we’ll have removed the last barrier to delivering hyper-realistic, fully immersive virtual worlds to any device, anywhere. From that point on, the possibilities will be limitless, bounded only by the extent of our imagination.

And this is today. Within five years, he told me, they’ll achieve absolute, indistinguishable-from-reality photo-realism. Regarding the ability of mobile devices to connect to the type of virtual world Rosedale envisions, he’s a little more conservative. In this case, the bottleneck isn’t computing power but the speed of Internet connectivity, which depends on more factors. Still, Libreri sees that being cleared within 10 years. And that’s it—we’ll have removed the last barrier to delivering hyper-realistic, fully immersive virtual worlds to any device, anywhere. From that point on, the possibilities will be limitless, bounded only by the extent of our imagination. Environmental consciousness may seem like a stretch, but researchers at Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab found that people who felled a massive, virtual sequoia used less paper in the real world than those who only imagined cutting down a tree.

Environmental consciousness may seem like a stretch, but researchers at Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab found that people who felled a massive, virtual sequoia used less paper in the real world than those who only imagined cutting down a tree.